Running Has a Whiteness Problem, and We Must Fix It Now

If the running community intends to make an impact on issues of racial justice, it has to start with the way it looks, inside and out.

By Ravi Singh

In the wake of social unrest, corporations make statements. Sometimes vague, sometimes emphatic. After the killings of Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd, the running community issued its own response in the form of hashtags like #iRunWithMaud, black squares on social media, and commitments to support causes tied to racial justice.

It was a unique moment to see such a range of industries that didn’t necessarily have direct ties to either incident acknowledge that the forces behind them—systemic racism and white supremacy—can manifest in so many ways and in so many fields. Some even went so far as to say the words “Black Lives Matter.”

Statements are a start, but are they actually leveraging the tools that running can to address systemic racism, especially given the sport’s increasing profitability and growing influence?

When brands are finished with platitudes—and many of these statements didn’t amount to much more, as they failed to actually name issues like police violence, housing and income inequality, or access to education—how will they exercise their clout?

Running is not all powerful, but it’s not powerless; its monstrous corporate and cultural capital has the ability to influence public policy, invest in communities, and foster inclusivity within its own circles. Why it’s currently failing to do so comes back to the near homogeneity of the sport’s participants, representations in its media, and leadership. The running industry itself is almost entirely dominated by older white men. More on that later.

How big is running’s financial power? According to Forbes, the global athletic shoe market is expected to be worth $88 billion by 2024. Currently, Nike would be the world’s 96th richest country.

Some statements that emerged in the wake of George Floyd’s killing expressed shock that the police could administer such cruelty. I, a brown skinned man who grew up in Toronto, was not. Black people were not.

That homogeneity, one found not just in running, results in a blind spot that obscures not only the most brutal manifestations of racism but also its rippling effect over centuries. If the running community intends to do something, it has to start with the way it looks, inside and out. If running’s leadership doesn’t understand the experience of Black communities and doesn’t include Black representation, it remains complicit in the vicious cycle we’ve been looped in for generations.

The running industry has often staked a claim to community building and advancing equity with charity challenges and fundraising efforts. That shouldn’t be dismissed, but the charity contributions raised from road races will not deliver the advancement we need.

What we need, in the words of William C. Rhoden, is a Marshall Plan for corporations to rebuild Black communities. That is, a redressing of the terrors of slavery, mass incarceration, and the destruction and looting of communities that has strangled the growth and flourishing of racialized individuals, a legacy fully present in both the United States and Canada. It means prioritizing access to health care (physical and mental), business grants for Black entrepreneurs,and partnering with local organizations to bolster and scale support programs for those facing barriers to education and job opportunities. It requires bold and unprecedented leadership, the kind that doesn’t always tie back to a corporation’s own bottom line, but to the wellbeing of communities.

Rethinking Representation

It’s been touted as a virtue of running that the sport is immediately accessible and presents no barriers to entry. The current running boom has invited runners of all ages, colours, skill levels, shapes and sizes to be a part of the sport’s social scene.

“According to recent surveys from Running USA and Athletics Canada, around 90% of those included in a sample of road racing participants identified as white.”

If the numbers are any indication, the welcome hasn’t been strikingly successful, or at least when it comes to race, the supposed openness and accessibility of running hasn’t resonated. According to recent surveys from Running USA and Athletics Canada, around 90% of those included in a sample of road racing participants identified as white. That amounts to an overrepresentation of nearly 30% of Americans (according to the 2019 census just 60% identified as white) and about 17% in Canada (72.9% of Canadians identified as white in the 2016 census).

The issue is not so easily grasped for those who have always seen themselves represented in branding and imagery, but the notion that you can’t be what you can’t see has been true for everyone at some point in their lives, but significantly more so for those on the margins. A dearth of representation and inability to identify with a movement drives away potential participants and reinforces outdated cliches and conceptions of who can be a runner.

“What’s irked me for decades in the industry is that every time you walk into a gym or yoga studio, there’s usually an image of a skinny white girl or a white guy with a six pack. It matters because the more you put those images out there, the more you reinforce the idea that white skin is the highest ideal,” says Dione Mason, a Toronto fitness instructor, trainer, and the director of the Toronto Carnival Run.

A recent analysis of running magazine covers and BIPOC representation led by Dr. Heather Hillsburg and Dr. Francine Darroch found that less than 15% of the U.S. and Canada’s two most prominent magazine covers over the last decade featured people of colour. Some publications managed year long stretches without a person of colour headlining an issue. For an industry that so often speaks the language of aspiration, wellness, and personal betterment, it’s telling how publishers choose to visualize these concepts.

People of colour also can’t only appear in running publications to shed light on and educate others about the challenges they face on the run because they are more than their struggles. These issues are important to highlight, but people of colour who run should be celebrated as runners and ambassadors of their sport just as their white counterparts are. Non-elite BIPOC runners can elevate the sport with their stories and create powerful waves of inspiration, but that requires a consistent presence in running media.

Ultrarunner and photographer Andre Morgan agrees that there’s an important sense of affirmation that comes with the ability to see yourself in a space. “When I capture people on the run and we have a shot that they really love of themselves, it’s empowering, a sort of avatar of what they can be,” Morgan says. If more running media would take on his philosophy, there’s at least a chance that this sense of empowerment can increase exponentially.

Morgan took it one step further on social media when he Photoshopped a fake cover of himself on a running magazine. “My sentiment behind it was that I shouldn’t have to apologize for how I look and that I could just be a runner as I am. It looks different than the typical cover, but I’m Canadian and a runner, so there’s no reason I shouldn’t be there,” Morgan says.

When discrepancies in health outcomes are considered, a trend which is showing itself once again in this pandemic, a sport that claims inclusivity ought to put a premium on reflecting the general population in its participation and in how it presents itself.

Rebuilding Corporate Leadership

Athletic brands have benefitted immensely from the Black dollar, Black culture, and Black athletes. The average Black or POC runner might be hard pressed to find themselves in mainstream publications, but high profile Black athletes have a presence. The leadership behind the scenes, however, is hardly representative of the population at large.

Take for example the immensely successful “We The North” campaign that became ubiquitous as the Toronto Raptors made their championship run last spring. Drawing heavily on images from Toronto’s diverse population and the aesthetic of the city’s rap and hip-hop scene, “We The North” certainly allowed Torontonians to see themselves in that moment and phenomenon, but the campaign was driven by creative agency Sid Lee, whose leadership is almost entirely white.

The “run crew movement” itself has borrowed from hip-hop’s DIY philosophy with many crews playing up their connection to local street culture and branding themselves as slick and underground. In major urban centres like Toronto, London, and New York, one can at least hope to see some of the diversity of these cities reflected on social media, but the question of whether or not running is finding a foothold in all communities still lingers.

Strava heat maps, which are admittedly not a comprehensive way of gauging who runs but can at least provide some indication of where running and run crews are concentrated, still shows a dividing line that finds running confined to areas that are upper middle class and white, which ought to prompt further research and discussion.

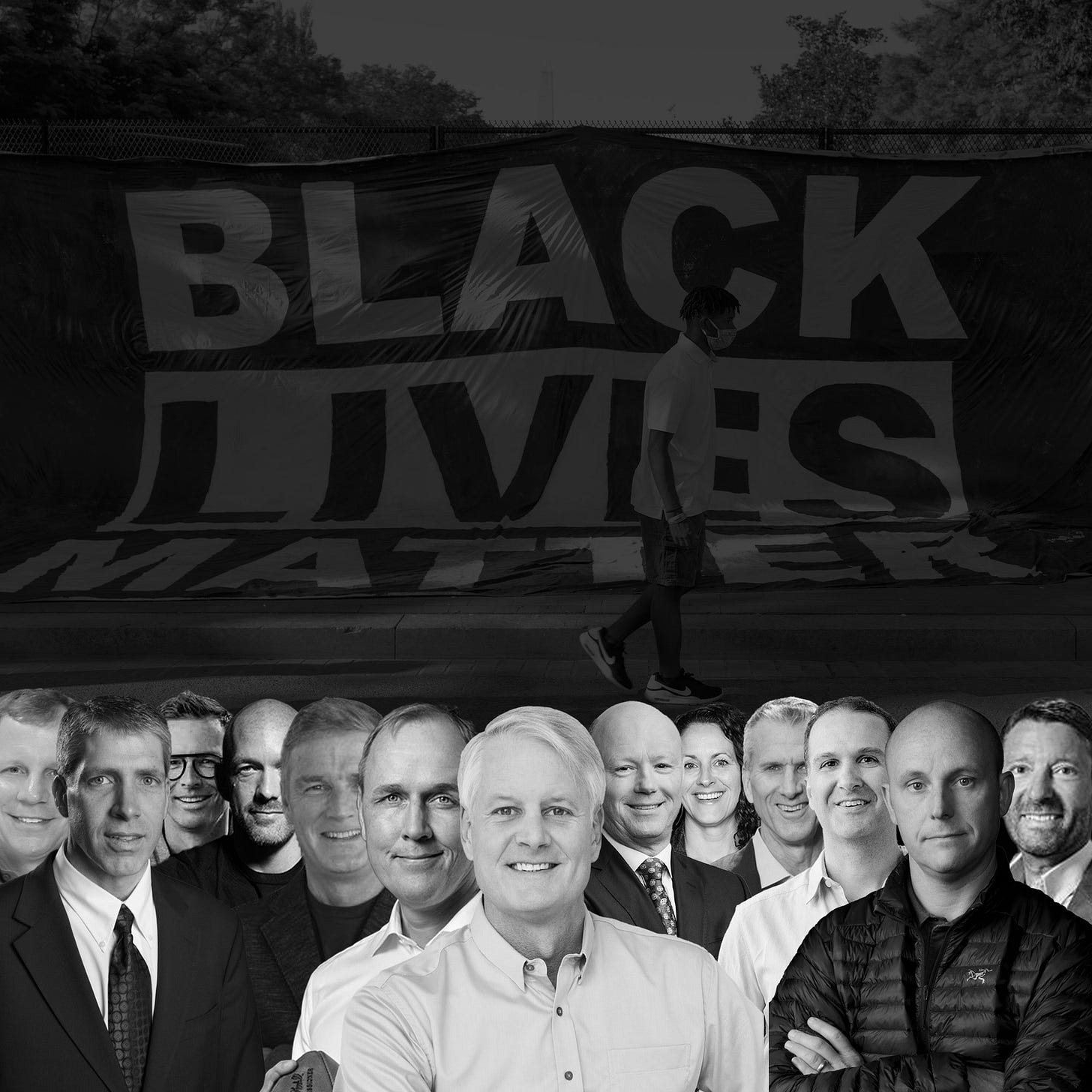

Below is an example of leadership composition across a selection of major running brands in North America.*

*Based on available data of executive teams and board of directors members.

The Presidents/CEOs of the brands above include one person of colour, Garmin Executive Chairman and co-founder Dr. Min Kai. Saucony and Hoka One One have white women as Presidents/CEOs, Wendy Yang and Anne Cavassa respectively. The remainder are led by white men, as is Strava.

Corporations, running brands included, have never been politically neutral. Campaign donations, corporate social responsibility initiatives usually encompassing a marginal investment in proportion to profit, and surely lobbying for and reaping the benefits of favourable tax policy, are regular and inherently political. Brands have now claimed a desire to do something meaningful, but that entails a change in the politics of running and a change in the sport’s leadership. “We start as the players on the field,” Morgan says. “But we have to be on the organizing part of it too. We’re the memes and sometimes the face on the website, but we’re also the people who have lived the experiences of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery,” he adds.

Networking is as vital as skill or experience in filling leadership positions, as companies often rely on referrals from current executives and employees. Our networks, personal and professionals, are often composed of those with similar ideology, background, and demographic characteristics. The contexts that tend to produce our networks, the schools we attended or social and community organizations we belong to, may have their own barriers to entry rooted in access to education, financial capital, accessibility, and personal connections.

“While brands continue to lean on Black culture in an almost predatory manner, Black individuals have little say over how that culture is used and in how corporations flex their political power.”

The effect is a de facto ceiling for Black professionals and people of colour, who are far removed from the intimate circles of leadership. While brands continue to lean on Black culture in an almost predatory manner, Black individuals have little say over how that culture is used and in how corporations flex their political power.

“If someone’s circle is all the same, nothing changes. Leaders need to make a deliberate effort to achieve balance and diversify their own networks,” Mason says. “We want to be in the circle but we can’t find our way in. We’ve been doing the work and our absence isn’t because of a lack of talent or ambition.”

The purpose of Black representation is not to save face, but to create the context for widespread change in the communities that have been ignored. It’s, hopefully, a means to drive an aggressive corporate social responsibility plan that doesn’t just make donations to causes of the moment, but invests in long-term strategies and political advocacy to address regulatory gaps in education, access to social services, access to affordable and nutritious food, over policing, housing, and career opportunities. Wes Moore, CEO of the Robin Hood Foundation, correctly pointed out in an interview on the Truth of the Matter podcast that these inequalities are the result of policy and won’t be changed without addressing policy.

What we need to see, across North America, is brands putting capital into long term community based programs that make running accessible to individuals of all backgrounds, which would necessarily tie back to political efforts addressing safety concerns based in policing, housing inequity, and lack of facilities and services.

It’s been a little over a month since the murder of George Floyd and even longer since we’ve known that corporate leadership, running included, has a race problem. Running’s claim of community building is being put to the test at this moment. For communities in crisis, social media statements and press releases won’t make the grade. Leaders in the running industry need to do the legwork and build their connections to Black communities, including in their leadership, and ensure full transparency in their efforts to address inequality, clearly demonstrating the reach and the impact of the dollars they’ve pledged.

Ravi Singh is a writer and runner from Toronto, Ontario.

Editor’s note: we’d like to acknowledge the complexity of identifying race via online images, and agree that this approach others those who are not white by applying race to categorize individuals as either white or BIPOC. We also understand that the term BIPOC does not does not specify individual cultural and ancestral differences.